Suhas Ramegowda and his wife Sunita had not always planned on the slow life they have now in Ooty. In 2015, the couple was living in Bangalore working in corporate jobs. They had acquired many of the trappings of a modern urban lifestyle and didn’t see any alternatives to staying on the treadmill.

There was a point that year, however, when they both began to wonder whether the material rewards were worth the chase.

“That’s when we began the journey,” Suhas said “of self discovery, and questioning what really made us happy.”

They gradually began to extricate themselves from the cycle they were stuck in – of work and consumption. As they spent more time together, and with their then 9 year old son, they found they no longer needed much in terms of external stimulation. They also embarked on a spontaneous road trip that took them from Mysore to Himachal and Varanasi and then back down to the hinterlands of Central India. The trip, with its rich encounters and experiences, validated their desire for an alternative lifestyle in a more rural setting.

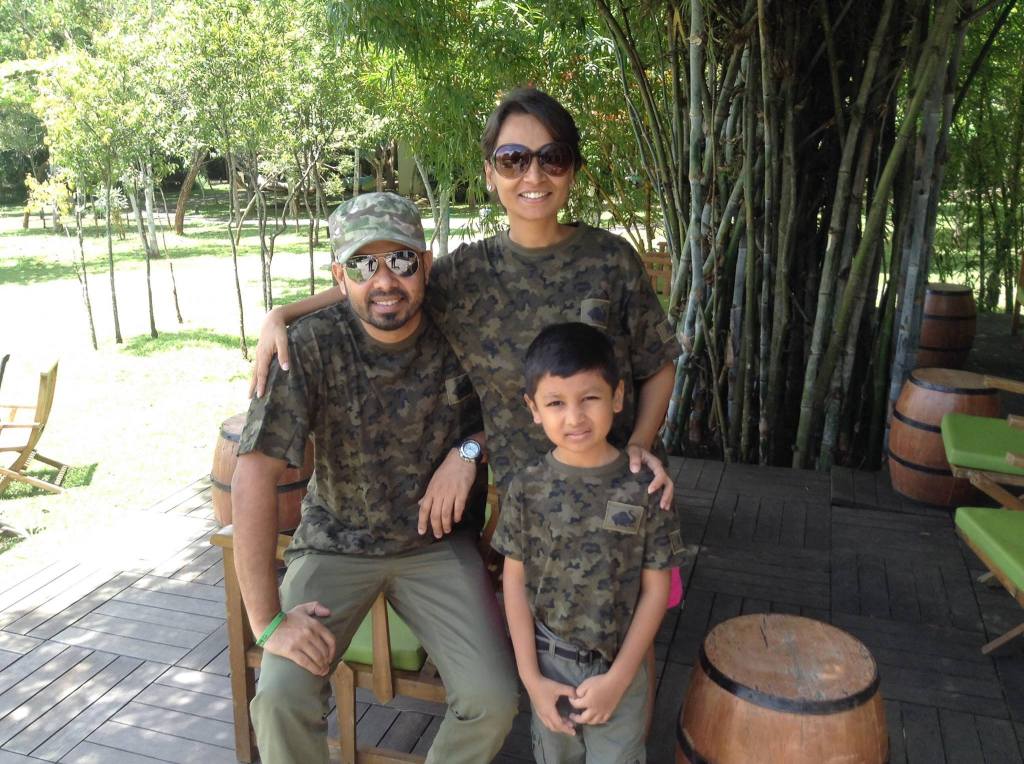

A chai break during their road trip

Suhas says: “We asked ourselves – if we don’t have that many transactions with the city, then why do we need to be here?”

And so in mid-2017, the couple quit their jobs, packed their belongings into five suitcases and made their way to the Isha Foundation campus in Coimbatore along with their son. They wanted to use their time there to recalibrate and ease into their new life. After completing a six month residential yoga teachers training course at Isha, they then pondered their next move.

During their yoga training days in Coimbatore

They considered moving to the Auroville township in Pondicherry but eventually found themselves in a small cottage in Ooty, set in the wilderness. During the first three months there, they fell in love with the area and quickly located a piece of land for their long term home. They built it themselves, sourcing mud and stone from the area around them, and getting the structure up with a little help from villagers they had gotten to know.

A dream house in the forest

Suhas said: “The nearest village was three kilometers away. We were harvesting water from the mountain stream and our electricity was solar powered. There were elephants, bears and other wildlife around us. It was truly living off the grid.”

Foraging for a daily snack

As they integrated with the community around them over the next two years, they became privy to the challenges that the locals faced. Their traditional ways of living had been impacted by increased development and commercialization in the region. With limited avenues for sustained income generation, most families struggled to get by. The poverty the couple saw around them felt more personal than what they witnessed during their city days. After all, these were people they interacted and ate with, and whose family functions they attended.

They weren’t sure what they could do about it until a chance conversation with a district forest officer of the Nilgiris got them thinking about their own skill sets and how they could leverage them to build a livelihood solution in the area.

Sunita was an accomplished crafter, skills that she had picked up from her mother. She and Suhas felt these skills could form the basis of a craft enterprise in the community – one that was focused on empowering women who were most vulnerable in families dealing with financial instability.

Starting with patchwork quilting and macrame as the initial crafts, the couple recruited a group of women and started the training in their living room. They offered a small stipend to those who committed to four weeks of training, in order to make it more economically viable for them to attend.

Their success in getting women to participate was largely due to the trust that they had garnered within the community by then. Suhas is convinced that the barriers are higher for many social enterprises that are based in cities and are remotely trying to manage their operations in villages.

He says: “There are so many instances where we get to identify a problem before it becomes a problem. We are able to course correct because we are here – paying attention and identifying patterns.”

Suhas is a Mysore native who speaks some Tamil now. And although Kolkata born Sunita has not picked up the language yet, communication is never an issue, Suhas says.

“We have made it here for seven years and Sunita has transferred so many skills without fully speaking the language. That’s because she was motivated to teach, and the women, to learn. Language isn’t a barrier in such an environment.”

Their son is now 16 and looking to chart his own path following an unconventional childhood of unschooling and peripatetic living. His parents would like him to volunteer, boost his social interactions and expose himself to the possibilities in the wider world.

Suhas says: “Our education system is pegged on conditioning and an emphasis on right and wrong. We wanted him to discover life through his own lens, with as little conditioning as possible.”

Read on to hear Suhas talk about the multi-pronged approach with their social enterprise, the part they feel is essential for tangible outcomes, and why he and Sunita want to continue to focus on building their solution for the Nilgiris.

How the Good Gift Got Off the Ground

Things just unfolded in an organic way. We call ourselves accidental entrepreneurs because we never really planned for any of this to happen. We thought we were going to retire to a quiet place, where we could grow our own food and live off the grid.

Patchwork quilting and macrame were the first two crafts we started with. But we had to figure out the commerce part of it for it to be self-sustaining. We wanted to ensure that the products we made didn’t burden the planet in any way. Lastly, we were clear we didn’t want to remove people from the traditional way of life. So the way forward in our minds was for them to be owners of the solutions we created.

We wanted to take it slowly in introducing people to ideas such as working for money, professionalism, timeliness, and quality. So while we were creating the patchwork quilts, we simultaneously got the sales channel up and running. Then during Covid, we got permission to operate as a livelihood unit and switched to making masks, apart from the quilts and macrame products. We would distribute the material, train women, get the items made, and then dispatch the finished products through India Post.

Athough the platform was now in place, we were not happy with the strength of our market linkages. We had a serendipitous encounter at this time with someone who’s well known in the social enterprise space. He told us that, while we had something special with the potential to be scaled, we had to go out and integrate ourselves with the ecosystem.

With his encouragement and nudging, we incorporated ourselves as a private limited company to enable market access for the products. We also registered Indian Yards Foundation as a Section 8 company, and as the not for profit wing of the enterprise.

We applied to a few incubators and had a chance to do venture incubation for nine months during 2022. There was a lot of learning from all of this, revolving around the nuts and bolts of building an enterprise. Around the same time, we were also able to raise funds from a few patient investors.

And that was how the Good Gift was born in early 2023.

The Good Doll: Designing for the Conscious Family

When we launched The Good Gift, we had multiple items in our lineup – coasters, tableware and a host of other home decor items. But, in the past year, our focus has been on fabric dolls based on market response.

Currently, almost 90% of the toy market is plastic. But there is a large and growing customer segment that is moving away from plastic and looking for sustainable alternatives in toys. These dolls speak to that segment. They are not new in terms of the design – they are essentially rag dolls, the kind our grandmothers may have made. In that context, they evoke nostalgia and there is a stronger emotional connect with them. We are making them using pre-consumer textile waste to stay in line with our ethos of sustainability and minimal waste. So we are essentially removing waste from both the textile and plastic fronts. We also realized that the product market fit is stronger with these dolls and it has been a good run with them over the past year.

How it’s Structured & Run

Indian Yards Foundation focuses on recruitment, upskilling and capacity building. The Good Gift does the market linkages. Separating the two made sense to make better use of time and resources. We have a comprehensive four week program that the women have to go through, with quality of output being a key parameter. Only when someone meets the quality metrics, can they move on to production. Most make it in four weeks, some in three.

Women keep walking through our door – we have not had to do any active mobilization. We started with five women and are at 70 today. I see us crossing 200 over the next two to three months. The whole model is decentralized. We source the materials for them. They take it home to work on the product. Now we are moving towards a hybrid model where 50% of the production will happen in our new manufacturing unit and 50% will be completed at home.

We have fashioned the entire production into an assembly line that can operate in the physical manufacturing unit as well as virtually, when work is being tackled at home.

There are about 12 of us on the team, including the trainers who are part of Indian Yards Foundation. Sunita and I are currently involved in both parts of the operation but plan to step back from Indian Yards down the road. We are looking for somebody to join us to lead that effort and run it as an independent entity. We will still be involved as board members but would like to hand over the reins to somebody else in terms of running it and building an organization for the next generation. We hope to be able to make that shift this year.

Upskilling Needs to Lead to Tangible Outcomes

We believe that just upskilling by itself is not solving the problem. There are multiple NGO programs focused on this aspect, without much attention to quality and income generation potential. There are some government schemes to help a woman gain some basic sewing skills. She may even get a low quality sewing machine through it. But it doesn’t put her on any consequential path to financial stability.

So we decided we will only step in to upskill when we are confident that we can enable employment and income generation at the end. That’s why we have trained only 200 women through Indian Yards Foundation when it was within our reach to train ten times that number. Out of the 200 women, almost 70 of them are actively engaged in work. We have also made it possible for a third of these women to procure quality sewing machines through a credit access platform called Rang De.

We will continue to impart skills that are monetizable down the road as well. It’s fabric arts today but it could be other skills in the future as we expand our portfolio.

The Goals: A Cooperative & Continued Focus on Livelihoods in the Nilgiris

This is a readymade platform for somebody who wants to do something entrepreneurial in this space. In the near term, we also plan to have a producer company in place with the women as members. We will then operate as a cooperative where members get paid not only for the work they do but will also have a share in the profits.

As long as we are on the board of Indian Yards, we plan to keep it focused on the Nilgiris. I think there is undue focus on scale at the expense of depth of impact in the social sector. We feel that if there is focused effort in a particular geography, the outcomes are much more tangible. We’re very open to documenting our learnings and making it available to other entrepreneurs in other regions who are looking to start something similar. There is a concept called social franchising in the West where people pick up ideas that are working in one region and then try and implement them in another region. While we’re not actively looking for such transactions, people are free to pick up our ideas and see how they can tailor it to other regions.

There are 83,000 households here, encompassing the rural and tribal landscape. I don’t think we can touch that in this lifetime. I’ll be very happy if we are able to touch 1,000.

Follow the work and updates of indianyards.foundation on Instagram; To view and shop for products, visit: https://thegooddoll.in/

To explore collaborations and partnerships, write to Suhas at suhas@thegooddoll.in

Leave a comment